From Lecture Halls to Vineyards: Celebrating the Retirement of Prof Johan Burger

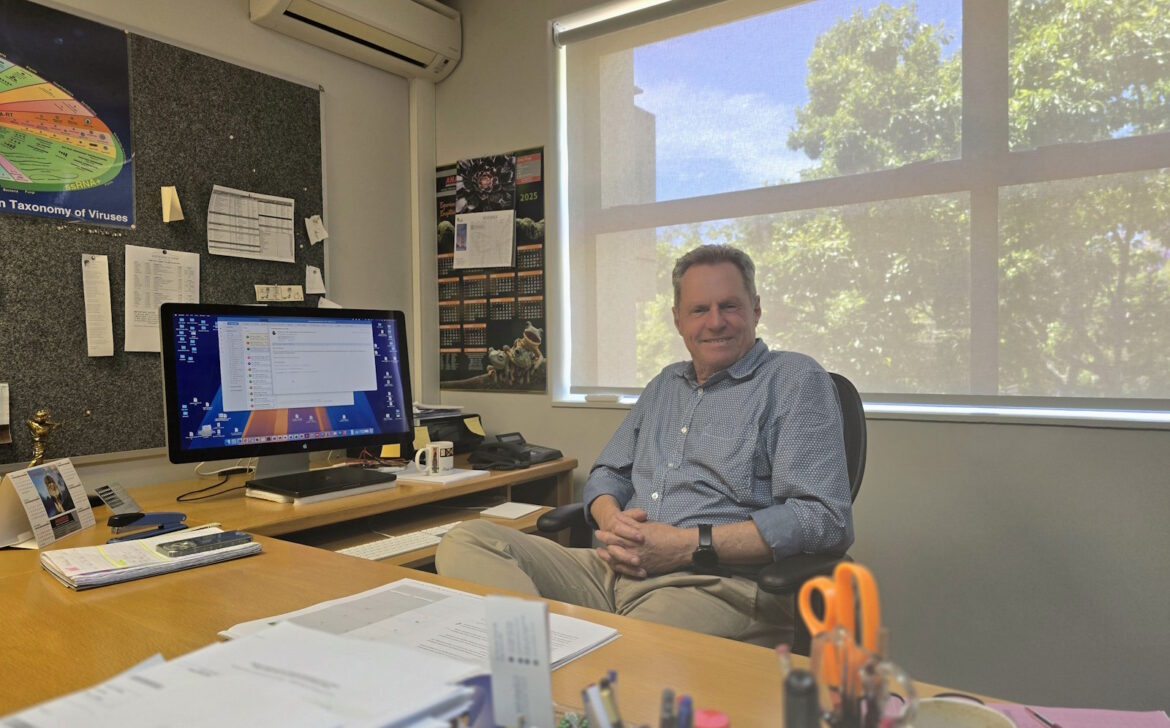

Prof. Johan Burger – a plant virologist has been a cornerstone of the Stellenbosch University Department of Genetics for the last 29 years. As a lecturer, he designed and taught foundational molecular genetics courses that shaped the scientific grounding of thousands of undergraduate students. As a former Head of Department, he provided steady leadership during pivotal years of growth and transitioning. As a supervisor, he trained and mentored hundreds of postgraduate students who now contribute to academia, industry and global scientific communities. Beyond his scientific work, Prof. Burger also served on numerous committees and advisory boards across academic, government and private sectors, contributing his expertise to national policy discussions, scientific review panels and industry collaborations. These roles extended his influence far beyond the laboratory, helping shape decision making in plant health, biotechnology and agricultural innovation.

Yet for all his accomplishments, it is his mentorship thoughtfulness, patience and deep humanity that has shaped a generation of scientists whose careers continue to reflect his influence. As he now steps into retirement, the Department reflects on the career of a professor whose teaching, research, and service have left an enduring mark on Stellenbosch University.

When asked what first drew him into plant virology, one might expect a carefully planned academic trajectory.

Instead, as Prof. Burger explained with a smile, his journey into the field happened “by chance.” His father wanted him to study medicine, consequently he applied and was accepted into medical school in Pretoria, as expected he boarded the train heading north but somewhere around De Aar, he realised with sudden clarity that this path was not truly his. So he did something remarkably bold: he got off the train, turned back to Cape Town (Stellenbosch), and abandoned medicine before it ever began.

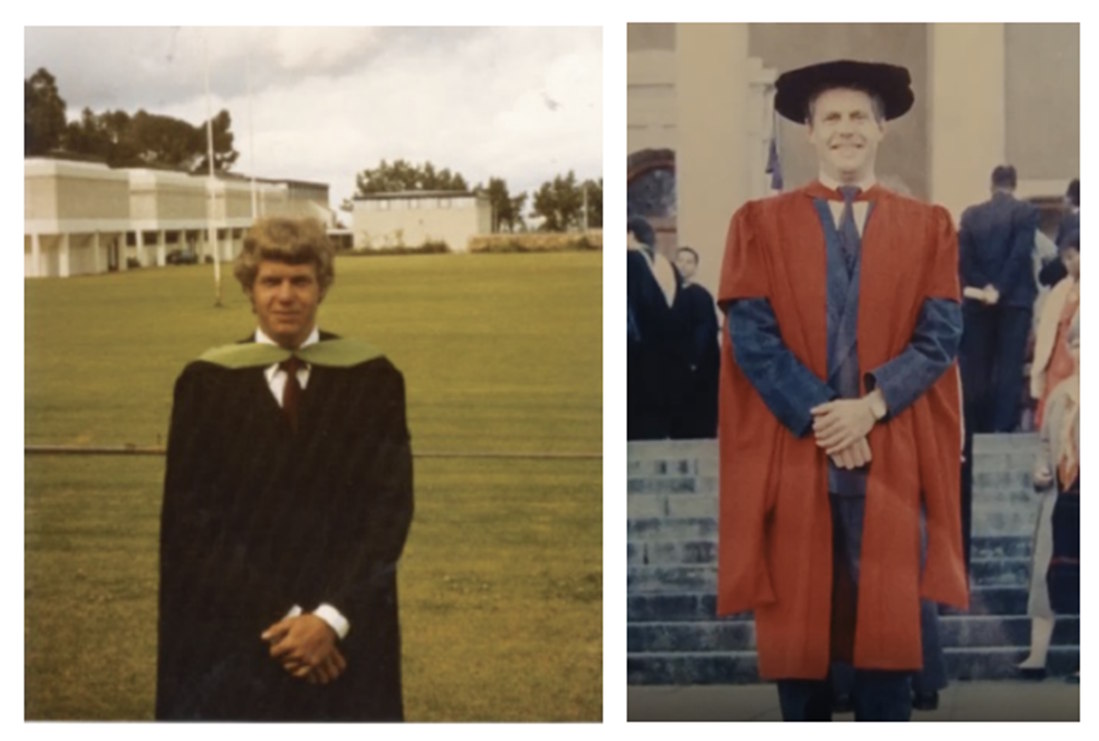

From there, he enrolled in Food Science at Stellenbosch university (1983), where an unlikely mentor changed everything: a lecturer remembered less for his teaching and more for his love of motorbikes. Their shared enthusiasm for motorcycles grew into a friendship, and this same lecturer became the first person to introduce him to plant viruses. “I was thoroughly hooked on virology after that,” he recalled. That early fascination ultimately led him to shift his academic path from Food Science to a BSc in Plant Pathology.

After completing his a BSc in Plant Pathology he fulfilled the compulsory national service required of young men in South Africa, a period he describes as “formative.” Noting that the leadership responsibilities he took on in a 33-year (part-time) military career, including eventually serving as a commanding officer of 3 Field Engineer regiment, helped shape his maturity and confidence rather than influencing his scientific direction. He later joined the University of Cape Town to study under Prof Barbara von Wechmarand Prof Ed Rybicki plant virology, where he entered a Master’s programme that eventually upgraded into a PhD focusing on “The characterisation of Ornithogalum mosaic virus”. With characteristic humour, he often notes, “You know, I actually only have two degrees to my name, a BSc and a PhD.”

Teaching Across Generations

When asked what it was like teaching generation after generation of students from millennials to Gen Z to early Gen Alpha Prof. Burger simply smiled and shrugged. “The labels never mattered”, he insisted. “Students are students.” they wanted to learn genetics. For him, that curiosity bridged every supposed generational divide.

One of his greatest joys was Genetics 244, an undergrad module he built entirely from scratch during his very first year (1997) in the department as a young academic. At the time, the module did not exist, and its creation marked his first real opportunity to shape how genetics would be taught to future cohorts. When he started, about40 students filled the lecture hall; today, the class sits at around 500. “It still astonishes me,” he said. The growth was never about prestige – it was affirmation that he had made the learning feel possible, accessible and exciting.

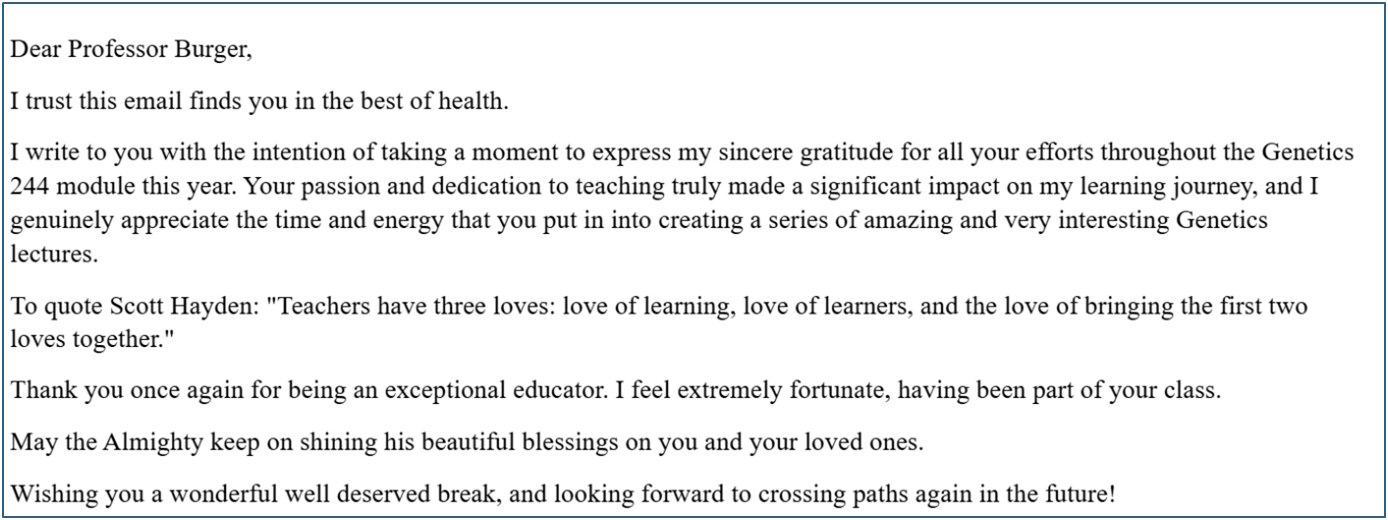

Yet the moments that meant the most to him came much later, often quietly, in the form of thank-you emails from former students. During our interview, he picked up one such email (the image below) and read it aloud. As he spoke, his voice softened and trembled ever so slightly. He paused, clearing his throat, clearly moved, though not quite to tears. “There is nothing more rewarding,” he said gently.

And of course, decades of teaching delivered its share of humour. One story he recalls with particular amusement is the day an UberEats courier walked straight into his lecture with a McDonald’s order “right there, during class!” he laughed. The moment was so unexpected and absurd that a student captured it on TikTok, where the clip quickly gained 8 254 likes, and 447 shares (click here to view the video). It became one of many stories that entered his personal folklore.

Research: From Vineyard Viruses to Old-Vine Mysteries

One of the most defining eras of Prof. Burger’s research took shape at Stellenbosch University through a collaboration with the renowned Kanonkop Wine Estate. Rather than highlighting a problem, the partnership reflected Kanonkop’s forward-thinking commitment to understanding one of the wine industry’s oldest questions: why do old vines produce wines with such exceptional depth and character? It is a question many vineyards in Stellenbosch and across the world continue to explore.

One of the most defining eras of Prof. Burger’s research took shape at Stellenbosch University through a collaboration with the renowned Kanonkop Wine Estate. Rather than highlighting a problem, the partnership reflected Kanonkop’s forward-thinking commitment to understanding one of the wine industry’s oldest questions: why do old vines produce wines with such exceptional depth and character? It is a question many vineyards in Stellenbosch and across the world continue to explore.

This curiosity set the stage for a pioneering study that became a cornerstone of Prof. Burger’s career. Working alongside his PhD student at that time (Dr Beatrix Coetzee) and collaborators, he helped generate one of the first comprehensive “viral maps” of a vineyard, a way of identifying the natural community of viruses that live quietly in vines and soils. As described in their publication, it was the first time a South African vineyard’s viral profile had been sequenced in such detail using advanced technology. Prof. Burger still recalls the moment they saw the results: “It was extraordinary,” he said, delighted by how quickly winemakers recognised the value of this new insight into vine health.

But the project didn’t stop at mapping. To understand how age influences flavour, the team compared the older, established vines (53 years old) with newly planted young vines (7 years old) growing right beside them under the same conditions. They collected leaves, stems and berries/grapes, studied how the plants developed over the season, and looked at the subtle biological differences between the two. One of the most striking findings was that the older vines ripened nearly two weeks later than the young vines, a small shift with potentially big implications for the layered, nuanced wines that old vineyards are celebrated for.

Through this collaboration, Kanonkop demonstrated the kind of curiosity and scientific openness that has long shaped its reputation: a willingness to invest in research that reveals, rather than hides, the quiet complexities of winemaking. And for Prof. Burger, it became a project that not only advanced the science of South African viticulture but also showed the power of partnership between industry and academia.

From Mentorship to Collaboration to Legacy of his lab

When Prof. Burger speaks about mentorship, his voice softens in a way that reveals just how deeply he valued it. “There is nothing more rewarding than supervising a student,” he said. Guiding them through uncertainty, watching them grow, and eventually stand confidently in their own scientific abilities was, for him, the true heart of academic life. His hope was always simple: that once they completed their degree in genetics, they would use it to do something meaningful. Many did, leading research teams, shaping national policy, and driving innovation across industry.

The moment that captured his legacy most clearly came on 12 November 2025. As he recounted it during this interview, his eyes filled and he paused, unable to hide the emotion. Without his knowledge, his former MSc and PhD students including post-doctorals and colleagues , some he had not seen in decades, had organised a surprise celebration in his honour. Several travelled long distances just to be there. When he walked into the room and saw all the faces of people he had once guided, he was overcome. “It was truly amazing,” he said quietly, wiping his eyes as he remembered it.

In that moment, it became clear that his greatest contribution was never a single experiment or publication. It was the people he had helped shape, and the scientists who now carry his influence into the world.

For Prof. Burger, collaboration was the lifeblood of his science. “One cannot progress in science without collaboration,” he said. Working with others not only strengthened the rigour of his research,it opened doors to new ideas, new techniques, and entire scientific worlds he might never have reached alone.

His career carried him across continents for workshops, conferences, and collaborations that often grew into lasting friendships. Among those he remembers most fondly are Prof. Assunta Bertaccini in Italy, ValerianDolja in the United States, and Prof. Giovanni Martelli of the University of Bari a towering figure in grapevine virology. He also spoke warmly of Prof. Marc Fuchs from Cornell University, whose expertise and partnership helped elevate the international standing of the Vitis group.

These were not merely professional connections; they were relationships built on trust, respect, and a shared love of discovery. “Science becomes better when done together,” he said a simple truth.

And perhaps nothing captures this better than the sprawling collection of lanyards in his office: badges from dozens of conferences, institutes, and countries. Each one marks a place he travelled, a talk he gave, a collaboration formed, a student met, a question asked.

When asked about the future of his research group, Prof. Burger responded with quiet certainty. There was no hesitation, only genuine pride in what the team had become. “I am excited to see where it will go,” he said, speaking with the ease of someone who has spent decades building not just a laboratory, but a scientific home.

What stood out most was his complete trust in the new leadership. He expressed deep confidence that those stepping into his place are capable, forward thinking, and ready to guide the group into its next chapter. “Such is the nature of science,” he reflected. “You work on discovery and impact, and when it is time to let go, you must do so with confidence.”

The Companions Who Shaped the Man Behind the Science

Behind every accomplished scientist stands a circle of support, and for Prof. Burger that support includes his companion Karin. She is central to this chapter of his life, and when he speaks of her his tone softens immediately. He describes her as “an amazing lady,” a phrase offered with unmistakable admiration. However his affection is just as evident when he speaks of his two sons. Having them, he says, was “a blessing,” and the pride he carries for them is unmistakable. His eldest son became a solar engineer working in sustainable energy technology, while his younger son pursued geochemistry and now works internationally for an exploration company in the USA. As he shares small stories about them, the ordinary details only a father remembers, a quiet joy settles into his voice. Their influence was never planned, yet it shaped him deeply, giving him perspective, resilience, and the grounding that only family can provide. As he reflects on them, he adds with heartfelt sincerity, “I am really honoured to have raised such wonderful sons together with my ex wife, who is also a strong academic.

Behind every accomplished scientist stands a circle of support, and for Prof. Burger that support includes his companion Karin. She is central to this chapter of his life, and when he speaks of her his tone softens immediately. He describes her as “an amazing lady,” a phrase offered with unmistakable admiration. However his affection is just as evident when he speaks of his two sons. Having them, he says, was “a blessing,” and the pride he carries for them is unmistakable. His eldest son became a solar engineer working in sustainable energy technology, while his younger son pursued geochemistry and now works internationally for an exploration company in the USA. As he shares small stories about them, the ordinary details only a father remembers, a quiet joy settles into his voice. Their influence was never planned, yet it shaped him deeply, giving him perspective, resilience, and the grounding that only family can provide. As he reflects on them, he adds with heartfelt sincerity, “I am really honoured to have raised such wonderful sons together with my ex wife, who is also a strong academic.

Recognition From the University Community

Prof. Burger’s contributions have also been formally recognised within Stellenbosch University. He received the 2025 Chancellor’s Award for research, acknowledging the depth and quality of his work over many years. The department later hosted a warm farewell celebration (see photos below), offering an opportunity for colleagues and former students to thank him, share memories and enjoy the moment together before he steps into this next phase of his life.

Looking Back, Standing Present, Moving Forward

As your departmental scribe and as a former undergrade student in Prof. Burger’s Gen 244 class and now his colleague,I can say without hesitation that he was and remains an eclectic lecturer with a rare ability to connect across generations. Even now, as a colleague, that same calm and grounded presence endures. Nothing seems to ruffle him; he brings humour, humility and an ease that has long made him one of the department’s most memorable figures.

When asked what comes next, he answered with characteristic steadiness. “I am not disappearing,” he said. “I will still be connected, just in a different way.” Retirement for him is a shift rather than a departure: continued affiliation with the research environment, balanced with long awaited time for family, golf and the freedom academia seldom allows.

As our conversation ended, Prof. Burger shared a few final reflections on teaching, science and the journey ahead. You can watch his message in the video below

Composed by M. Le Roux